In April 2021, Jonathan Dudley and I had an [update: AWARD WINNING!] article "Why the case against abortion is weak, ethically speaking" published in Salon. While the main goal of the article was to advocate for ethics education concerning abortion, the article presented an argument for the view that at least most abortions are not immoral and so should not be illegal or criminalized.

Clinton Wilcox posted a rather long response (I think it's 3 times the length of our article) which I am finally going to respond to, although in an unavoidably selective and incomplete manner. To try to be more efficient for anyone reading this, I'm just going to comment "in text" on the original article, with my comments between *** and in purple. I do recommend anyone read his article in the original form before reading my commentary.

NOTE: AT SOME POINT SOME NUMBERING OF THE PARAGRAPHS STARTED GETTING ADDED TO THIS: I DON'T KNOW WHY AND I DON'T SEEM TO BE ABLE TO REMOVE IT. SORRY!

+++

It’s been a while since I’ve published an article to the blog, and there are a couple of reasons for it. Number one, many more people tend to listen to podcasts than read articles (especially since podcasts can be listened to on-the-go), so I’ve been concentrating more on our podcast, Pro-Life Thinking. A second reason is because it’s very rare that anything interesting is published in the popular blogosphere which is worth responding to. There are only so many times I can call out pro-abortion bloggers for fallaciously attacking a pro-life advocate’s character instead of his argument or to call out their assumptions without proving their case. Once in a while something catches my attention and I think it deserves a response.

Salon has published an article written by Nathan Nobis and Jonathan Dudley called “Why the case against abortion is weak, ethically speaking” (which you can read here). But as one of my pro-life philosopher colleagues said about it, it contains many, many leaps in logic. In fact, their tagline reads: “Many medical procedures are ethically similar to abortion — without the outcry. Why?” This tagline makes it seem like they’re just not very knowledgeable about the literature (I don’t know much about Jonathan Dudley, but I know that Nathan Nobis has engaged with the work of at least Frank Beckwith on the issue). This is just a ridiculous question that ignores some very serious nuances of the discussion.

*** FYI, I'll just mention that titles and taglines aren't usually from authors: editors develop them. But this seems like a fine title: it's informative and accurate to much of the content of the article. It does not, however, suggest anything about the ethics education advocacy urged in the article.

Nobis and Dudley (hereafter ND) start off by complaining about the recent spate of pro-life laws being proposed. That’s as it should be, as abortion, itself, is unconstitutional and needs to be overridden by the court (for an excellent explanation of why abortion is unconstitutional, read this article by legal scholar John Finnis). However, their beef in this article is not with the legal fight but with the pro-choice movement’s stark avoidance of any discussions of ethics. While I do agree that the pro-choice movement caring more about the ethical discussion would certainly help elevate the discussion and give pro-life writers who care about intellectual engagement more to write about, the case isn’t as cut-and-dried for the pro-choice position as ND believe it to be. In fact, the best philosophical arguments rest squarely on the pro-life side of the debate.

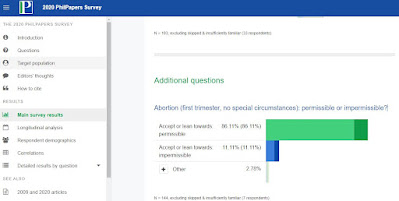

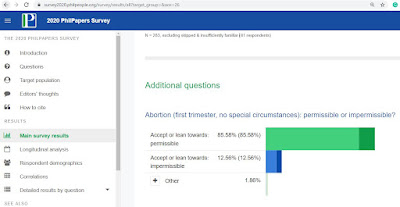

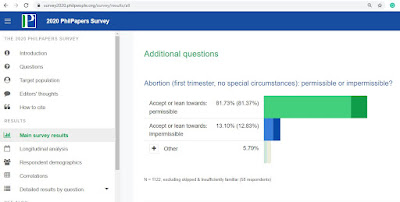

*** Something that's interesting is that most professional philosophers (who have earned PhDs in philosophy, typically publish in philosophy and typically teach philosophy) disagree with that judgment. In the 2020 PhilPapers survey it looks like only about 10-15% of philosophers who took the survey believe that early abortions are typically wrong. So it is highly dubious that "the best philosophical arguments rest squarely on the pro-life side of the debate" (emphasis added): experts reject that claim.***

ND assert the arguments attempting to establish abortion is murder are demonstrably weak. However, there are no arguments forthcoming about why these arguments are weak.

*** Surely there are arguments: reasons are given for our conclusions. Some think they are not good arguments, but there are arguments. ***

Instead, they look at two situations they consider similar and argue since there is no pro-life outcry over these situations, there should be no outcry against abortion, either. But if the pro-life arguments that abortion is weak really are “demonstrably weak”, as ND claim, they should be able to pinpoint exactly what claims pro-life advocates make and show why they are weak.

*** But there were "exact pinpoints" given: that claims that beginning fetuses are "innocent" are either false (or meaningless, since "innocence" just doesn't apply to beings that are in no way agents) and that the claim that it's prima facie wrong to kill or end the lives of (innocent) human beings or biologically human organisms admits of more exceptions than is often noticed. ***

At best, if you point to two similar situations and show there is no outcry, you can say pro-life people are inconsistent. It says nothing about whether or not their arguments against abortion are sound.

The first of these two allegedly “less controversial” topics is organ donation. The second is regarding anencephalic fetuses (anencephaly is a severe defect in which the baby is born without parts of the brain and skull. While many anencephalic fetuses die during gestation, many also do survive to birth. Those who survive to birth don’t typically survive more than a few days after birth.

For this next section, I think it will be more helpful to quote each of ND’s paragraphs verbatim to show exactly where they go wrong.

First, in every U.S. state and most countries, if a person elects to be an organ donor, their organs can be removed for transplant when that person suffers complete brain death — even if their body is still alive. Organ harvesting involves cutting living human beings open and their organs being removed one-by-one until, at last, the heart is detached and the human being dies, having been directly killed by the procedure.

This is hardly an uncontroversial point, though. While most pro-life people do tend to support organ donation, a large number of them don’t support organ donation if it will kill the donor. If a person is merely “brain dead”, she has irreversibly lost all of her brain function, higher and lower — but the person is still alive.

*** Comment: many would say that the person is done and gone in such a case. Why don't you want your love ones to become brain dead? Because they, the person that they are, will end, even if their body stays alive. At least that's what many think here.***

Calling it “brain death” is a misnomer, since “brain death” is a state of dying, not death. Because of this, many bioethicists are even skeptical of the concept of “brain death”, itself (e.g. David Albert Jones in his 2001 book Organ Transplants says a patient’s body may still be alive while brain dead, and Leon Kass in his 1985 book Toward a More Natural Science says “the primary stimulus to seek a new definition of death was the need for organs for transplantation” (both of these quoted in Christian Bioethics: A Guide for the Perplexed by Agneta Sutton, p. 167), and this point by Kass was also stated by neurobiologist Maureen Condic in her paper “Life: Defining the Beginning by the End” for First Things, which you can read here). So the concept of “brain death” is still a controversial one, since the person’s body is still alive and able to be kept alive through life support.

*** Comment: I don't see that these appeals and quotes show that brain death is a controversial concept, but here's some research on the topic.

That being said, no matter how one lands on the question of organ donation, there are differences here that may justify organ donation while not justifying abortion. For example, in organ donation, the organ donor consents to having his organs harvested and given to someone else. The fetus does not consent to having his life taken to benefit his mother.

*** Yes, but fetuses cannot consent to anything, so any kind of demand for this is a demand for something that's impossible. Not doing the impossible is no fault against anyone.

(It's also worthwhile that the ultimate significance of consent for organ donation is unclear: if a healthy young person consents to being killed and their organs taken, should we do or allow that? Probably not. Suppose some dies but didn't consent to donate their organs: would it be wrong to use their organs to save others' lives? Maybe not, and so some propose that only when people explicitly withhold consent to use their organs after their death (since, hey, they don't need those organs anymore, and so perhaps that withholding consent would be irrational?) should we not use someone's organs: explicit consent is not needed.)

Another important difference is that when someone has irreversibly lost their brain function, their life is essentially over. They are dying and cannot be restored to health. If the person could be restored to health (e.g. if he is in a reversible coma), then surely it would be unethical to remove his heart, killing him, even if he has consented to being an organ donor. In contrast, a fetus is at the very beginning of his life. Comparing organ donation, a procedure to take someone’s organs who can no longer use them to give to people who need replacements, with abortion, a procedure meant to kill a human being to make the mother’s life easier in some way, is fallacious.

*** No, all comparisons involve things that are similar and different. So, of course the organ donation and anecephaly cases are different from abortion, in some ways, yet they are similar in some ways also.

So, although fetuses are not brain-dead, they (like brain dead bodies) are also not "brain alive" or "brain birthed." And so, although not in these words, we offer a principle like this:

If a body is not brain alive or is not brain birthed, then it is prima facie permissible to kill that body.

What this shows is that most people recognize that it’s not always wrong to kill human beings. This is true even when those human beings are considered “innocent,” as human beings used for organ donation are often categorized. This is a first step in undercutting the pro-life argument.

Very few ever argue it’s always wrong to kill human beings. Only extreme pacifists believe this. The pro-life argument is not that it’s always wrong to kill human beings, it’s that it is always wrong to intentionally kill innocent human beings. I have explained this personally to Nobis on a couple of occasions, and I know pro-life sociologist Steve Jacobs has explained this to him, too.

*** So you may not be familiar with what many anti-abortion people actually say and the exact words they use: they often insist that just because fetuses are "alive" makes abortion wrong and that just because fetuses are "human" makes abortion wrong. They do offer up these simplistic arguments: observing that these arguments are simplistic and that they can and should know about better arguments is helping them learn more about the issue and how to better communicate about it.

But he seems to insist on continually misrepresenting the pro-life position in this way, as he did in his book with Kristina Grob.

*** For more how in philosophy it is very common to begin with simple arguments, explain why they are inadequate, as one works toward more complex arguments, see A Response to Clinton Wilcox's review of 'Thinking Critically About Abortion' at "Secular Pro-Life" here, please.

And here ND are also misusing the term “innocent”, in that they are not using it in the way pro-life people use it. When a pro-life person says it’s wrong to intentionally kill an innocent human being, they mean “innocent” in the sense that they have committed no crime deserving of death.

*** The point was that something can't be innocent if it can't do anything, much less a crime: the term just doesn't apply: e.g., calling a rock or some living cells in a dish "innocent" doesn't make sense, since they can't do anything.

It is permissible to put a murderer to death but it is impermissible to put a fetus to death, who has committed no capital crime; indeed, who is much too young to even understand right from wrong.

*** Or just understand. Not understand anything, but understand, period.

So this is not the first step in undercutting the pro-life argument, and anyone who follows it is, frankly, taking bad advice.

A second relevant set of cases involves anencephalic infants, or babies born with severely undeveloped brains. These babies usually do not live long, and the widely accepted medical practice is to let these infants die, providing palliative care only, even though they could be kept alive by a machine. This ends their lives, but it is not wrong.

Here is ND’s appeal to the case of anencephalic infants, and they, again, misrepresent the situation. Yes, the accepted medical practice is to provide palliative care to anencephalic infants and allow nature to take its course. This is the same palliative care we’d give any terminally ill patient at the end of that person’s life (assuming that person has rejected euthanasia as an option, which pro-life people would also say is the unethical taking of a human life). So their life does end, but their lives are not ended by an action done by those providing palliative care. ND are simply twisting language to make it seem like this is similar to abortion — they’re trying to jam a square peg into a round hole. They are failing to understand the difference between killing [NN: an innocent] someone [NN: usually] an act of murder) and allowing someone to die (which can be unethical or it can be ethical, depending on the situation). Certainly there is no ethical wrong in allowing nature to take its course if you have no way of saving that person or restoring that person to health. Allowing a person to die whom you can’t save is not the same thing as killing someone who is healthy to benefit someone else who wants that person dead. This is just an absurd comparison.

*** The issue is basically this: what if an anencephalic infant could be kept (biologically) alive: would it be wrong to let that infant die? Most will answer, with good reason, "no," and we think the answers here suggest that early abortion can be permissible. Like anencephalic infants, embryos and beginning fetuses also not "brain alive" or "brain birthed." And so, again although not in these words, we offer a principle like this:

If a body is not brain alive or is not brain birthed, then it is prima facie permissible to kill that body.

The ethical insight gained from these two common medical practices is that not all human beings have a right to life that trumps all other considerations: it is not always wrong to end the lives of even innocent human beings, if they lack what would make ending their lives wrong.

Let me just quickly recap. Abortion is not like organ donation because in organ donation the person consents to it, is dying, cannot be restored to health, and so no longer can use his organs. Abortion kills a perfectly healthy (in most cases) individual because he is in the way of something the mother wants (usually, to not be pregnant). Furthermore, abortion is not like anencephaly because allowing someone to die that you can’t save is not the same thing as killing a perfectly healthy individual (in most cases) because they are in the way of something another person wants (again, usually, to not be pregnant). ND are using two cases that are not like abortion and trying to draw ethical insight from them. But these cases are useless in trying to tease out some ethical rule for treating human fetuses.

*** No, a rule or principle can be found among them: one was mentioned above (twice) and here's another way to present an argument based on such a rule:

- Organ donation procedures and the treatment of anencephalic newborns are morally permissible.

- If organ donation procedures and the treatment of anencephalic newborns are morally permissible, then it’s permissible to end the lives of biologically human organisms without functioning, consciousness-making brains.

- If it’s permissible to end the lives of biologically human organisms without functioning, consciousness-making brains, then early abortions, of fetuses without functioning, consciousness-making brains are morally permissible.

- Therefore, early abortions, of fetuses without functioning, consciousness-making brains are morally permissible.

To respond, here’s what one could do, regarding each premise:

- Argue that organ donation procedures and the treatment of anencephalic newborns are not morally permissible, for whatever reason(s): e.g., these are human, these are human organisms, these are human beings; there is always some chance of recovery, etc.

- Argue that a different generalization, or none, at all, is suggested by the cases in (1). Explain why that's a better generalization to draw than what we propose.

- Identify a relevant difference such that (3) is false and justify the relevance of that difference: e.g., clearly, fetuses and the organ donation and anencephalic newborn cases are different: fetuses typically have a type of “potential” that the other cases don’t; fetuses, if “left alone,” so to speak will continue living, etc., but how is that relevant? Why would that make killing them wrong? Real, developed answers are needed, and the answer that “because they are human organisms” isn’t going to cut it, at least not for those who accept (1).

the human beings in question do not have brains capable of supporting consciousness, awareness, or feelings. Since these common medical practices concerning organ donation and anencephaly are morally permissible, so are most abortions.

This is actually very misleading. The people in question do have brains capable of supporting consciousness, awareness, or feelings. In the case of the “brain dead” individual, the brain has irreversibly lost its ability to engage in these functions, but it is certainly a brain capable of supporting it (just like your eyes are still capable of sight even if you end up going blind; this is evident in the fact that in many cases, such as cornea transplants, we can actually restore sight that has been lost — the main problem is it is currently not medically possible to restore brain function to one who has lost it or was unable to develop it properly).

*** This is an odd way of understanding potential or what's possible in these sorts of cases: "He can't see, but he could see, if his eyes, which he can't currently see with, could see." In some ways this move is comparable to someone claiming that every cell has the potential to become a person, since various (potential?) technologies could make that happen.

And in the case of anencephaly, their brains are also capable of supporting these functions, but due to a severe birth defect their capacity for these functions has been blocked due to the birth defect. It is not medically possible, at least currently, to help people in these situations, but they are still human beings and thus are still capable of performing human functions, even if these functions have been blocked due to illness, injury, or something else.

I could go deeper into the philosophy of why these people still have these functions, but it’s not necessary.

*** It seems like these cases are special cases because the individuals here lack these functions and they can't have them, at least how "can't" is usually understood in ordinary and even medical contexts.

What is enough is simply to show that ND are ignoring the fact of human development. It’s true that the “brain dead” individual has irreversibly lost his brain function and the anencephalic infant was never able to fully develop his capacities to flourish as humans should. But these are not similar situations to the normally healthy fetus, in which the fetus is at a very early stage in his develop and certainly has a brain capable of supporting consciousness, awareness, or feelings. We know his brain is capable of supporting these things because he will grow up to engage in these activities. If his brain was incapable of supporting these functions, he would never grow up to perform them, much like a hedgehog will never grow up to engage in rational thought (Sonic, notwithstanding). It is not a tragedy when a hedgehog fails to grow up to be a rational individual — it is a tragedy when a human being fails to do so, which is why anencephaly is considered a birth defect. It is not how the individual is supposed to be.

*** Yes, a difference among these cases is the types of potential that are relevant: e.g., a fetus has potential(s) that a brain-dead human organism does not have, at least on an ordinary way of viewing the cases. But maybe not, given what's said above, since it's noted that the a brain-dead human organism has the potential for being a "normal human being" so to speak if, say, God intervenes or technology allows for their brain being repaired or whatever. So, on that suggestion, there are potentials either way.

But, of course, there are challenges with appealing to potential: potential X's need not be treated as actual X's, and if someone if a potential Y, but that requires someone else's help, in general that someone else is not obligated to provide that help.

After this section, ND try to anticipate objections to their arguments but their attempts at responding goes off the rails.

ND does correctly say pro-life advocates will argue this conclusion doesn’t follow, given differences among the cases. But the responses they anticipate are not what I would think the most common responses would be.

Pro-life intellectuals argue that organ donors are not really “human beings”. ND point to a talk by Peter Singer, Alan Shewmon, and Patrick Lee, moderated by Robert P. George, as defense of this point. Singer, of course, is pro-abortion and pro-infanticide. Lee and George are pro-life philosophers, and I’m not familiar with the work of Alan Shewmon, though I have seen him cited in other works.

*** You should look him up: he's important here.

I’m a bit skeptical that Lee and George hold this view (that “brain dead” individuals are “not really ‘human beings'”), but it’s not necessary for me to address this position. This is not a position that I hold, and it’s not a position held by many other pro-life intellectuals. ND are taking one potential response and acting like it’s the only response given by pro-life advocates. I am a hylemorphist, in the vein of David Oderberg and Ed Feser. I believe that as long as the organism is alive, it is a human being, a person worthy of rights and respect. So I agree with ND, that organ donors are human beings. They are living human organisms with heartbeats. I agree. But no, the pro-life position does not imply organ donation practices are wrong. It does imply that organ donations which kill the individual is wrong because it’s always wrong to intentionally kill an innocent human being.

- But donating other organs, such as kidneys, would not be wrong, so long as the person is not killed in donating the organ. So ND’s first point can simply be rejected because it’s not held by many pro-life intellectuals and they draw a faulty conclusion from what they think is implied by the pro-life position. This first point fails to make their case.

- Pro-life advocates recognize anencephalic infants as human beings and argue it would be wrong to harvest their organs. But either both brain dead humans and brainless infants are human beings or neither are. Again, another point I agree with. Both of them are human beings and it is wrong to act in such a way as to intentionally kill them. Plus, anencephalic infant organ donation has a further wrinkle in that anencephalic infants cannot consent to donating their organs.

- *** Yes, that's impossible, given what they are actually like.

- One might argue that a parent can consent to donate her child’s organs to children in need, and this is true in certain cases. If a child is dying and cannot be restored to health, it may be permissible for a mother to consent to donating the child’s organs. But if a mother takes her own child’s life, clearly this is not a licit situation in which a mother can consent to donating her child’s organs. Again, this point can safely be rejected because it’s not a point argued by many (perhaps even most) pro-life intellectuals. And in my case, I hold that both of these human beings are human beings and I hold my views consistently regarding how to treat humans at the beginning and at the end of life.

- Organ donation and anencephalic newborns involve human beings who have lost their potential for valuable futures; yet fetuses have lives, or potential lives, before them and so have rights to those lives. And they are innocent. Here ND almost raises relevant objection, but the problem is they’re only responding to one possible pro-life rejoinder, and one that’s not even the strongest that could be made. Don Marquis does, of course, make an argument against abortion from the fetus’ having a valuable future, and that’s an important argument in the literature.

*** Interestingly, while Marquis's arguments are typically thought by philosophers to be the best arguments against abortion, few enthusiastic advocates of abortion agree with that. Perhaps this is because Marquis's arguments can justify abortion in some circumstances (e.g., if the future baby would have a very grim future) and euthanasia and have other implications that many abortion foes reject.

But there are many objections to his arguments also, including the denial that abortion literally denies a fetus of a valuable future. (See section 5.1.5.). These objections do tend to be rather abstract though.***

- But talking about brain dead people and anencephalic infants is not about their loss of potential for a valuable future — it’s about their loss of their capacities. It’s not one’s valuable future that makes one a person, the fetus’ having a valuable future is just one more reason why it’s wrong to kill them. What makes one a person is his nature which grounds his ultimate capacities for things like rationality, consciousness, self-awareness, etc.

- *** We agree on the "nature" language, but think our nature is fundamentally mental: our essence is related to our conscious experiences, not our bodies. This is a view with rootes in Descartes and, especially Locke, and even Swinburne advocates for such a view.

3a. Fetuses are not “innocent” because it implies the potential for guilt, and that’s only true of persons. Here ND actually beg the question against fetuses being persons. They have failed to establish this point so they can’t simply assume it. Plus, when pro-life people speak of fetuses being innocent, it’s in the context of not having done anything worthy of being executed for, like committing a murder. *** Again, only a person could do anything like this: "innocence" in this sense presumes "person." (computer glitch isn't allowing a return here)

3b. “Personhood” is a controversial concept, but the organ donation and anencephaly cases can help us understand it. This point is ND’s weakest, overall. Their argument amounts to: It is (usually) wrong to end the lives of persons because they have a right to life. It is not wrong to kill an organ donor or anencephalic infant. Therefore, they are not persons. But this argument is seriously question-begging. They are assuming it is not wrong to kill organ donors or anencephalic infants, but they certainly haven’t made a case for it.

*** You are correct that people who think that the organ donation procedures we describe are wrong and that anencephalic infants cannot permissibly be allowed to die would reject the first step in our discussion. But that's not most people, and it's even not most people who oppose abortion, as we note. Given that, we ask why these procedures are permissible and propose that the best explanation applies to beginning fetuses also, entailing that early abortion is typically permissible.

They alluded to the fact that anencephalic fetuses and brain dead individuals are no longer able to engage their faculties, but their comparing these two individuals to fetuses is a category mistake. These two individuals are prevented from engaging their consciousness because they’ve irreversibly lost it, but the fetus will be able to engage his consciousness once his brain develops enough. Plus, ND haven’t justified just why having consciousness-enabling brains makes one a person, when having the inherent capacity for consciousness, just lacking the present ability to exercise it, doesn’t. There are a lot of assumptions being made here that ND hasn’t justified in their article. Contrary to ND, I would argue it is always wrong to intentionally kill innocent human beings. Organ donors and anencephalic infants are innocent human beings. Therefore, it is wrong to intentionally kill them. My position is consistent,

*** Yes, consistency--lacking contradictions--is a virtue, but consistent views need not be plausible, all things considered, and not all (and even any!) claims in a consistent view need to be true or reasonable. So, again, many even people who oppose abortion are going to deny what seems to be your judgments about organ donor and anencephalic infant cases, and their reasons may have implications for, say, how embryos can be treated as well as early abortions.

being grounded in the nature of human beings and the fact that these two individuals still are human beings. ND’s position is inconsistent, arguing that you can pick out situations and justify denying them personhood rights based on those situations.

*** No, there is nothing inconsistent in anything we said: there's no formal contradiction among the claims or even any tensions.

In fact, they are human beings at a very early stage in development before they are rationally able to understand right from wrong. Additionally, ND’s analogizing fetuses to human eggs or tissue is just wrong-headed. No one refers to human eggs or tissue as “innocent” because they are not capable of doing anything they could be guilty for. Fetuses are often treated by pro-choice people as if they are guilty of inhabiting the woman’s womb against her will (see, e.g., Eileen McDonagh’s book Breaking the Abortion Deadlock). Fetuses are referred to as innocent because they are human beings, and how you treat something depends on what it is and what it has done.

*** This is a new proposal for what innocence is: earlier innocence depended upon not doing anything wrong; now just being a human being makes something innocent, even though there are human beings who are not innocent, given that they have done something wrong?

It is not always wrong to kill a human being (e.g. you can kill someone in self-defense) but it is always wrong to intentionally kill an innocent human being, and if fetuses are innocent human beings, it is wrong to intentionally kill them, too. That’s an argument that works even if you want to leave the question of personhood out of the debate. ND’s last point, that for something to have a potential future it is required that “someone” be a person is just puzzling. My dog, Roxy, is not a person.

*** Is Roxy then like a rock, a thing? Or is she like a plant. again a thing? If we must classify her as a person or not a person, which is she closer to? Obviously some argue that she's closer to a person than not. Denying this might be comparable to, as anti-abortion people see it, the "rationalizations" that some people give in defense of abortion.

But surely she has a future ahead of her. She’ll wake up tomorrow, she’ll eat her food, she’ll go outside and lay in the sun, etc. Something does not need to be a “person” to have a future, and this is a point Marquis has made repeatedly. Making the “future of value” argument a personhood argument misses the entire point of the argument.

ND’s last major section has to do with making positive arguments for the permissibility of abortion. They start off by asserting “the simple failure to show that abortion is wrong might be enough for that”, but this is surely mistaken. Why should abortion’s permissibility be the default position and not its impermissibility? I could just as easily say pro-choice people have failed to show that abortion is permissible so it should be illegal,” but that clearly wouldn’t be a very satisfying argument. Not only that, again, it’s question-begging. Just because someone can’t show why ~X, that doesn’t prove X and vice versa. As an example, even if no one could prove God exists, that doesn’t, then, prove God doesn’t exist.

ND state the ethical framework most medical ethicists use to determine whether a human being has moral rights is whether that individual has interests. That’s all well and good, but just because “most” medical ethicists use that framework doesn’t mean, ipso facto, that’s the correct framework. Plus, ND are ignoring two key points here: 1) interests are important, and we should strive to help people obtain their interests. But interests are not the only, and maybe not even the most primary, consideration about how to treat someone. ND speaks of “interests” as promoting their well-being, but the problem with that is people have different opinions of what their well-being entails. Often people have selfish interests that they pursue at the cost of the interests of others. 2) Someone can have interests without being directly aware of them. If an infant has an inheritance coming to him, but the executor of his estate squanders his inheritance, he has surely been harmed, even if he never finds out about it. So fetuses definitely have interests — there are ways in which you can act which promote the fetus’ flourishing and ways in which you can frustrate the fetus’ flourishing (most obviously by killing him in abortion). Fetuses have interests, and arguing that they can’t currently exhibit consciousness or self-awareness does not, in any way, show that fetuses don’t actually have interests, or that they don’t have interests we’re obligated to respect.

*** Yes, there's a lot to say about what interests are and who and what has them. But on many common views here, never-been conscious entities don't have interests. Trying to carefully explain why that might be incorrect is a worthy task.

It’s true that rights protect interests, but we can’t protect our interests at the expense of someone else’s interests. I agree with ND that we ought to act in such a way as to contribute human flourishing. But grounding it in interests, as ND does, is not helpful, for the reasons listed above. Grounding rights in human nature gives us an objective standard for promoting human flourishing, as flourishing as human beings is common to all human beings. It is not merely up to one’s opinion about what their interests are. If rights are grounded in my interests, that means I have the right to mistreat other people for my own good.

*** Your next line suggests that the previous line is based on a misunderstanding of what an interest-based theory of rights would entail, since other people have rights too. (Rights theorists and advocates are not egoists).

But clearly I don’t have this right, especially since other people have rights and interests. If rights were based in interests, there would be no way to exhibit most rights because most rights frustrate the interests of others (e.g. if I get hired for a job, I have just frustrated the interests of the person who didn’t get hired). It just doesn’t make any sense to ground rights in interests, since interests can, and often are, selfish.

So ND’s assertions that minds matter, not heartbeats or human DNA, is only part of the story. A conscious and self-aware mind are not necessary for having interests. Plus, ND are mistaken when they assert fetuses don’t have interests. Of course they do — they are just not presently aware of them. But by virtue of being a biological organism of a certain kind (i.e. human beings), they have interests by nature, and it is this nature, not their interests, that ground their rights. This is the only way to truly respect people’s rights. If rights are grounded in interests, it is impossible because interests are often selfish and it is not usually possible to act in ways that don’t frustrate an individual’s interests. But all human beings require the same basic things for flourishing, such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. This means it is entirely possible to respect other people’s rights, because I respect their ability to flourish, while also seeking my own rights to flourish as the kind of thing I am, i.e. a human being.

ND are also mistaken when they say fetuses have rights to the women’s bodies, labor, and time only if explicitly granted it. This is the same kind of argument that justifies slavery, the Holocaust, and every other type of atrocity.

*** Slavery involves someone falsely claiming that they have a right to someone else's body (and labor) and acting accordingly. The same could be said about the Holocaust and other atrocities. I don't see how this would support thinking that a fetus does have a right to someone else's body.

Fundamental rights mean no one can grant or take them away — we have these rights by our nature, not by government or by personal fiat of someone who is stronger and can kill or harm us if they so desire. The fetus has the right to the woman’s body because he has a right to life, and you must kill the fetus to remove him, and also considering in the vast majority of cases the fetus exists in the woman’s body because of a volitional act she engaged in. You can’t invite someone on your property and then kill them, claiming it was in self-defense or you were allowed to kill them because you had simply revoked consent to their being there.

Thomson’s insights are not without controversy, however. Some respond the violinist case is somewhat like a pregnancy that results from rape, since there’s no consent involved, but claim that pregnancies that don’t result from rape do give fetuses the right to the woman’s body because, they argue, the woman has done something that she knows might result in someone existing who is dependent on her.

Thomson, however, had other cases that partially address this type of concern: e.g., if someone falls in your house because you opened a window, they don’t have the right to be there, even though you did something that contributed to their being there; and, more imaginatively, if people sprouted from “people seeds” floating in the air, and you tried to keep them out of your house but one managed to get in and became dependent on your carpet for its gestation, that resulting person would not have a right to be there, despite your having done something that led to that person’s existence.

To quickly recap, as I’ve shown here, ND’s case falls apart. The situations of anencephaly and organ donation are not analogous to the act of abortion, and their reasons to justify abortion don’t work, they wrongly ground rights in one’s interests instead of one’s human nature, where it should be grounded, and they simply don’t adequately anticipate good objections to their position.

I commend ND for wanting to elevate the discussion of abortion but this article goes about it the wrong way. In order to have a discussion on ethics, you need to properly understand what the pro-life position argues. ND unfortunately misses the mark.

*** Thanks for your comments! I hope anyone who read this find this interesting and informative! If there's anything that anyone wanted commentary on but I didn't say anything about, please let me know! NN